By Luna Peng

You’re vast and you’re sad

What is identity? Something formed when an individual enters public. Optical figures, names, ethnicity, physical being, a kind of carrier, a way to distinguish, labels, barriers drawn between you and others. Representation of your being. Acknowledgment of your existence. Your voice. Your record of being or used to be alive. It seems like an unescapable problem for every human being to solve. To be seen and be proved and be valid. We yearn for a self and thus pile up symbols on one another attempting to carve out something, at least something, representing ourselves.

In this age of the internet, this whole process is customized into an online version with an unexpectedly huge public, which makes every individual participating in it feel a bigger opportunity to be heard and understood but also a more frequently felt disappointment. Then how do we know who we are? How can we find somewhere to dwell in among this vast jungle of representation? How do we deal with the upgrading anxiety alongside feeling “not fitting in”? Maybe, maybe this could be an answer.

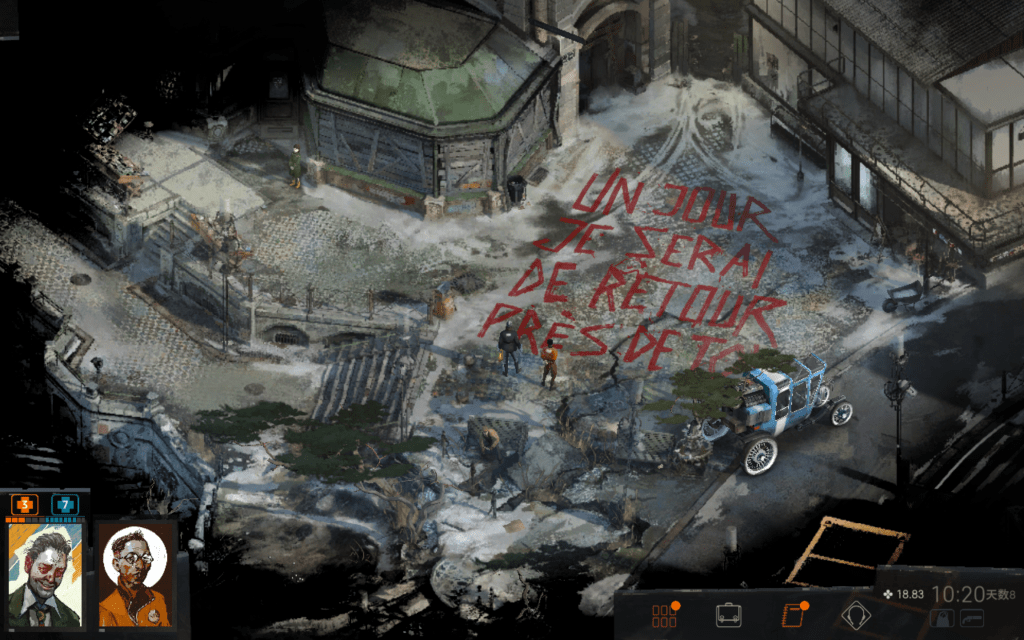

Disco Elysium is a cRPG game released by ZA/UM in 2019, known for its heavy literal texts and simple mechanics of clicking answers in conversations and dice rolling as a deterministic rule.

Entering the game, you’ll find out you woke up in a small hotel with a serious headache and no understanding of the condition you’re in like a newborn baby. You walk out of your messy little room and find out that you’re a detective—-a police officer. But what kind of cop are you? Why is it like this? Who are you?

This is the first and probably the most important problem you’ll encounter when playing Disco Elysium. Fortunately, you can choose what kind of cop are you. Or not? Well at least you get to give yourself an initial setting of the percentage of different characteristics before jumping into this whole new world. As long as you start to interact with the characters in the game—which is the primary mechanics of this game—you’ll never find a way to walk out of this maze the person you want it to be, or at least you think you’d be.

Disco Elysium provides the player with an excited level of agency while as frightened as well. You’ll need to make lots of choices to move the plot forward, and more than one time I feel like I was being interrogated. Where do you stand politically? What is your morality? What about relationships with others? Work ethic? All of the choices you make help you discover a little bit more of yourself. This kind of agency could be relieving but also crucial at the same time. It is scary to see what kind of person you are, but what’s comforting is that there is no correct answer to each of the questions so you can’t possibly be a “wrong” person. And it is just a game! It’s a process of identification that has no cost which very sweetly makes you don’t have to worry too much. When you woke up in this game world at first glance, when you walk to the mirror and see a stranger’s face—your face, you start the journey of finding yourself.

But here lies a dilemma: can we find out our identities as something hidden for some time? If so, then identity will be something predetermined and tagged to its owner before they even exist. Plato said if we are talking about a table there must be a FORM of the table, an original table, existing in our minds, allows us to tell a table from a chair. So now the question turns into this: is there a perfect version of you who is ready to be released in this life? What are we identifying when we are identifying ourselves as some identities? At the end of the day, what do we really possess, an identity or a bunch of words?

“…it is this way with all of us concerning language; we believe that we know something about the things themselves when we speak of trees, colors, snow, and flowers; and yet we possess nothing but metaphors for things — metaphors which correspond in no way to the original entities… A word becomes a concept insofar as it simultaneously has to fit countless more or less similar cases — which means, purely and simply, cases which are never equal and thus altogether unequal. Every concept arises from the equation of unequal things.”

–Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense” (1873)

Is it possible to conclude your political inclination simply as Capitalism or Communism or any other ideology? With the plot developing and more and more choices being made when playing Disco Elysium, you’ll probably make some unexpected decisions when encountering a huge amount of complex, controversial scenarios. To this extent, Disco Elysium is not a tool that allows you to discover what’s your political opinion but a place where your political identity is constructed, happened, or born. It is an accelerated process of identification.

Disco Elysium is a game that hands a mirror to its player yet not asking them to stay. Miriam Hansen wrote in Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film about how movies as a media formed an illusion of identification welcoming audience to participate in its narrative to reproduce capital. “In terms of ideological effect, the creation of a spectator through classical strategies of narration was essential to the industry’s efforts to build an ostensibly classless mass audience, to integrate the cinema with an emerging consumer culture.” (85) Considering the concept of spectatorship, a game, compares to film, probably constructs a more natural and seaming less process of identification for its players. An RPG game usually has a storyline that every player would follow and get to experience. Instead of watching a predetermined story from a certain perspective, participating in it seems more attractive and immersive. So why don’t people fall into the world of Disco Elysium?

Astrid Ensslin in her book Literary Gaming suggests that literary game placed itself from a distance from its player, “in order to expose and undermine gamers’ uncritical willingness to subscribe to commercial games’ . . . encoded (racist, sexist, classist, capitalist, etc.) ideologies” (40). Case builds on to her point and particularly refers to Disco Elysium, saying that “because of the ways that digital games have the potential to encourage players to connect closely with the avatars they inhabit—such as Harry Du Bois in Disco Elysium—while also reflecting on the ways that their own ideologies and perspectives mirror and differ from those characters in the manner Ensslin describes, games also challenge traditional conceptions of the self as singular and cohesive in a way that could have profound effects on contemporary cultural conceptions of narrative.” (88)

Other than giving answers from a game studies point of view, Daniel Vella contributes to this discussion of Disco Elysium from the aspects of literary analysis, combining it with the idea of Bakhtin’s polyphonic concept which is originally raised by him to analyze Dostoevsky’s novel. “He argues that “all of Dostoevsky’s major characters, as people of an idea, are absolutely unselfish, insofar as the idea has taken control of the deepest core of their personality.” (Bakhtin, 87) Vella argues that different ideologies in Disco Elysium are externalized as Harry Du Bois’s self-conflicting thoughts that frustrate him as well as the players. “With the decision to traverse from the unified self to a multiple subjectivity, a space for a polyphonic monologue was created that – in response – invites the player as an essential part of the discourse. Unable to find universal truths or authors’ convictions as a point of reference, they are forced to hear out the arguments, look for contexts, and make an informed choice as a result. Since such choices hardly ever bring undoubted successes, and their outcomes usually range from the catastrophic to the almost mediocre, there is no obvious strategy for playing Disco Elysium with an optimal playthrough in mind. And since there is no one “right” way to finish the game, the options that weren’t chosen remain with the player as parts of the character’s internal monologue no-one acted upon, potentially valid and true until proven otherwise. They stay as parts of the conversation within the game, regardless of whether they were chosen or not.” (Vella, 102)

Giving this kind of agency to its players, Disco Elysium allows everyone to be anyone. There’s no right answer, no perfect strategy, and no illusions. It refuses a mass, faceless spectator. A refusion to capitalized. The effort of resisting can be seen but the fact that it is gradually eaten up by capitalism is also unignorable. “The game was nominated for four awards at The Game Awards 2019 and won all of them, the most at the event. Slant Magazine, US Gamer, PC Gamer, and Zero Punctuation chose it as their game of the year, while Time included it as one of their top 10 games of the 2010s. The game was also nominated for the 2020 Nebula Award for Best Game Writing.” Awards are being given, reputation being gained, merch being sold, studio members having legal issues…All while capitalism is being criticized in the game. Is it possible for us to escape a narrative like this? How can we break it through?

Conor McKeown provides a nuanced way to approach the solution by connecting the game to post-human theory, which emerged as the development of artificial intelligence and the exploration of other forms of life.

“Perhaps while humanity has previously considered the other in relation to the self, the awareness of a decentralized context forms the basis of a posthuman way of thinking about alternative forms of reality. This means that human awareness is not needed or necessary for experiencing a reality but rather is one of a seemingly endless array of possibilities.” (III, James E. Willis., 2023)

As McKeown notes, Disco Elysium’s “particular character construction system, imaginative setting and replay mechanics resonate with posthuman theory.”

“I have argued that Disco Elysium combines a system for producing a sense of self through heterogenous automata reminiscent of Hayles’ earlier publications, with a world that literalizes the material non-Newtonian indeterminacy within which Barad suggests agential cuts produce resolution. These two systems, however, are played off one another through the games use of repetition that, following Ferrando, suggests an extradimensional interplay of materiality. This suggests a possibility that the heterogenous automata are not producing a singular coherent form of Harry but, rather, recon- figuring multiple potential resolutions with no one ‘true’ or enduring Harry per se. This extradimensionality is, I think, an important new avenue for posthuman game studies as it presents a solution to troubling questions of entangled selves and others, such as presented in the work by Wilde, Janik and others mentioned in this paper. Rather than discussing play as an agential cut that forms one configuration of entangled selves and others, we can embrace the notion that the multi-dimensional agential cut is non-destructive; there are hosts of different configurations possible, and each has a material role to play in the existence of the other.” (McKeown, 78-79)

Taking this very abstract idea back to the topic, what might be useful is that it offers a new perspective in an anti-humancentric view, considering gaming as one of the alternative realities. Though the technology today is not ready for a thoroughly realistic virtual reality, Disco Elysium is already trying to create a game world that is as complex as our real life in terms of ideological conflict and historical development. By saying this I’m not denying the uniqueness and independence of the game and defining it as a recreation of a real-life conversation, but rather want to point out that the experience one can have playing it won’t be less heavy and valuable than a real-life experience.

Going back to the very beginning, how does Disco Elysium participate in the process of identification and dealing with anxiety? Maybe it’s just to make a decision. To go somewhere. To play. I mean, if gaming could be life, why can’t life just be a game?

Work Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Case, Julialicia. “Our Bodies, Our Incoherent Selves: Games and Shifting Concepts of Identity and Narrative in Contemporary Storytelling.” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, vol. 10, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 71–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5250/storyworlds.10.1-2.0071. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

Disco Elysium. ZA/UM, 2019. Steam, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch.

Ensslin, Astrid (2014). Literary Gaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT P.

III, James E. Willis,. “Posthumanism.” The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society, edited by Debra L. Merskin, Sage Publications, 1st edition, 2020. Credo Reference, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/sagemass/posthumanism/0?institutionId=577. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Mckeown, Conor. ““What kind of cop are you?”: Disco Elysium’s Technologies of the Self within the Posthuman Multiverse” Baltic Screen Media Review, vol.9, no.1, 2021, pp.68-79. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsmr-2021-0007

Plato. Republic. Ed. Robin Waterfield. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, 1 Jan. 2019. Web. 15 May. 2023.

Vella, Daniel and Cielecka, Magdalena. ““You Won’t Even Know Who You Are Anymore”: Bakthinian Polyphony and the Challenge to the Ludic Subject in Disco Elysium” Baltic Screen Media Review, vol.9, no.1, 2021, pp.90-104. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsmr-2021-0009

Wikipedia contributors. “Disco Elysium.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 15 May. 2023. Web. 15 May. 2023.